Just over four years ago, the Scotch Malt Whisky Society of Canada was launched in Calgary, Alberta by the husband-and-wife team of Kelly and Rob Carpenter. Among their many achievements since then is the fact that a year later they somehow navigated a pile of legal red tape the size of the Rocky Mountains to launch a liquor business in BC, at which point I became a member.

After a while my growing pile of scribbled-in tasting booklets wasn’t giving me the hard data I was looking for, so I decided to take on the already formidable task of tracking the Canadian SMWS releases. With an average of seven bottles released every month and five years of operation in the backlog, there was a daunting amount of information to ferret out and convert into a useful format.

But ferreted out it has been, and now resides in a convenient Google Spreadsheet which you can access here. Grab a glass of a spicy & dry cask-strength whisky and let’s see what we can find in there.

The Data

Most of the data came from the individual bottle pages on the Canadian SMWS website, with some missing data coming from other websites.

One of the primary pieces of data I was interested in, the date that the whisky was released in Canada, isn’t listed anywhere on the website. I was going to have to do some legwork of my own. Luckily, I’ve been a member of the SMWS since it launched in BC in October 2012, and every month members get an email listing the current outturn. As I never delete emails, I was able to go back through them all and pull out the information I wanted.

But wait! Before June 2013, the email only contained highlights of each outturn, and not the whole thing. For those eight months I had to fall back on the booklets I got from attending the monthly tastings (which I’ve hoarded because… um… anyway moving on). I’d missed a few though so even that wasn’t a perfect source, and of course I didn’t have any information regarding outturns before the BC release. Happily Kelly from the Society saw my plea on Twitter and generously stepped in with the missing data. Thanks Kelly!

The Basics

So after getting all of this data in one place, what can it tell us?

I have 371 bottles listed through to (and including) December 2015. These include all the bottles released through the 49 outturns, as well as some special bottles released for festivals etc.

The oldest bottle released so far is 35.71 “Like a Hug From Your Mum”, a 40-year-old Speyside beauty from the December 2013 outturn. The youngest are a couple of 4-year-olds, one a grain whisky (G13.1 “A Complete Revelation”) and the other being 129.2 “Humbugs in a Horse’s Nosebag”, a release from Islay’s most recent distillery (until Gartbreck begins operation in 2017).

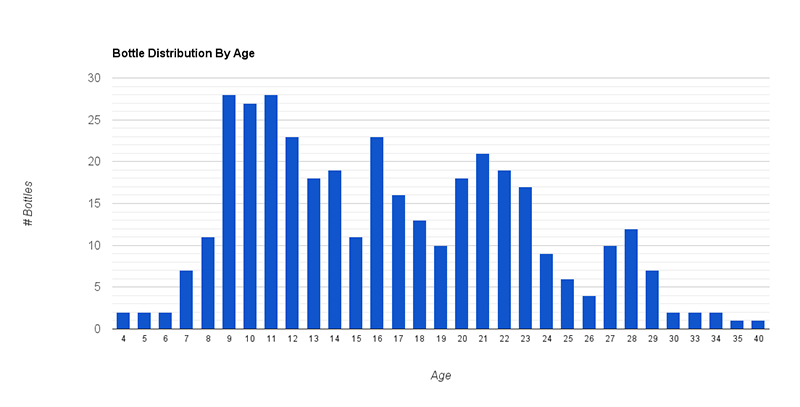

The most common age range is from 9-12 years old, with a couple of spikes around 16 and 21 years old. The mathematical average is 16.6 years old.

The lowest strength release is 40.6% ABV, just squeaking over the line to qualify as whisky, for the 26-year-old 35.53 “Old Jazz Bar”. If this had been left in the cask much longer there’s a chance it couldn’t have been released as a single-cask whisky. On the other end of the spectrum there’s the rum release R5.1 “Mint Humbugs” at an eye-watering 81.3% ABV. The second and third place releases in the ABV chart are also rums, both over 70%; the highest-strength whisky is 127.39 “Intensely Tasty” at 66.7% ABV. The average of all releases is a rather high 57.2% ABV.

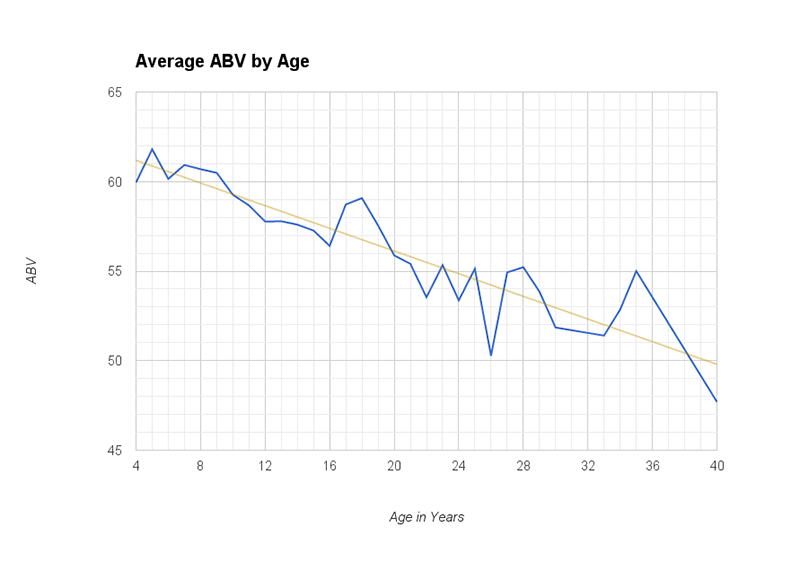

Considering the relationship between age and strength leads us into the first really interesting illustration we can pull out of the data. Generally, we expect whisky to reduce in strength the longer it’s kept in the cask. The alcohol evaporates more quickly than the water, leading to the famous angel’s share. In some cases, such as a warm climate, the inverse can be true and the spirit can actually increase in strength – you’re probably seeing that happening with the very high-ABV rums mentioned above, aged in the Caribbean. This is definitely not the normal case with Scotch whisky though!

In other words, taking the bottlings as a whole, we’d expect to see that the older the whisky, the lower the average strength at bottling would be. What would that look like with our SMWS dataset?

The graph is spiky given our low sample size, but the relationship is beautifully clear even so. The younger whiskies are close to the strength they would have been at when placed into the cask (usually 63.5% for malt whisky), and the older ones have seen significant alcohol evaporation.

The Casks

The Casks

Let’s turn our attention to the casks themselves. The data provided by the SMWS is a bit inconsistent with, for instance, “refill hogshead” often being used instead of the more specific “refill bourbon hogshead” and “refill sherry hogshead”, or even “second-fill hogshead”. But we can generalize, maybe make an assumption or two, and take a look at some high-level figures.

Of all casks listed, hogsheads (capacity 238 liters) are the dominant type with 145 instances, or 39.1% of the total. Barrels (200 liters) are next, with 104 or 28%. Butts (500 liters) come in third, surprisingly close to the barrels total at 98 (26.4%). The remaining 6.5% are made up of puncheons (320 liters), gordas (600 liters), and port pipes (500 liters).

As for the bourbon/sherry/other types breakdown, I’ll make the assumption that unless otherwise explicitly stated, “barrel” or “hogshead” means ex-bourbon. Using that, I come up with 232 bourbon-matured releases, 124 sherry, and 15 “other” (port, wine, or virgin oak casks). That’s pretty much in line with what I’d expect, given current trends across the industry as a whole.

It would be interesting to see if the more unusual casks have been used more often in recent years, given the modern dearth of sherry casks and even the supply of bourbon barrels being more constrained and subject to high demand, but the dataset is just too small to see if that’s true. Maybe in a few more years.

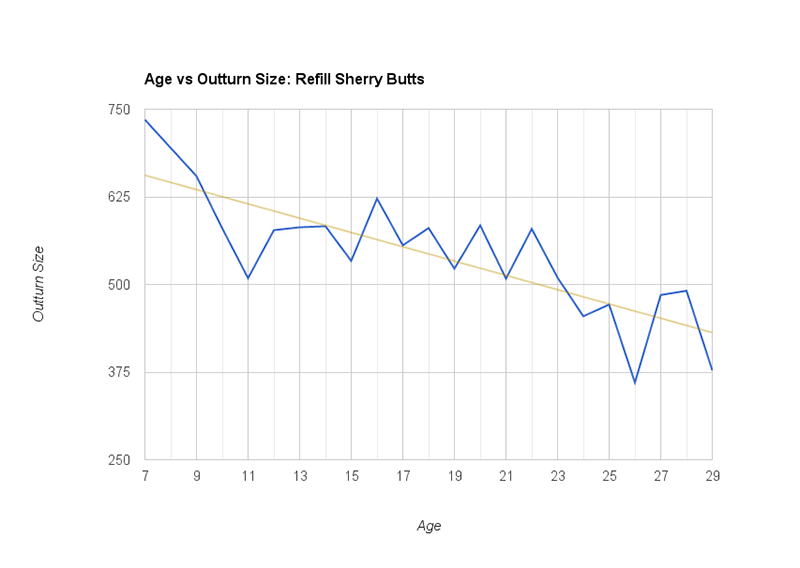

The number of bottles in each outturn runs as expected, with the larger casks producing more bottles. There’s a shallow but definite trend of greater age resulting in smaller outturns too, even given this small sample size.

The Distilleries

There are definite trends when it comes to the distilleries the Canadian branch of the SMWS is getting hold of. There are 159 distilleries across all release categories, and in 49 outturns (plus a few special events) we’ve seen releases from 74 unique producers. Many of the remaining ones are closed, no longer sell to the Society, or are obscure and release few bottlings even through the UK branch, so we’re not doing too badly there.

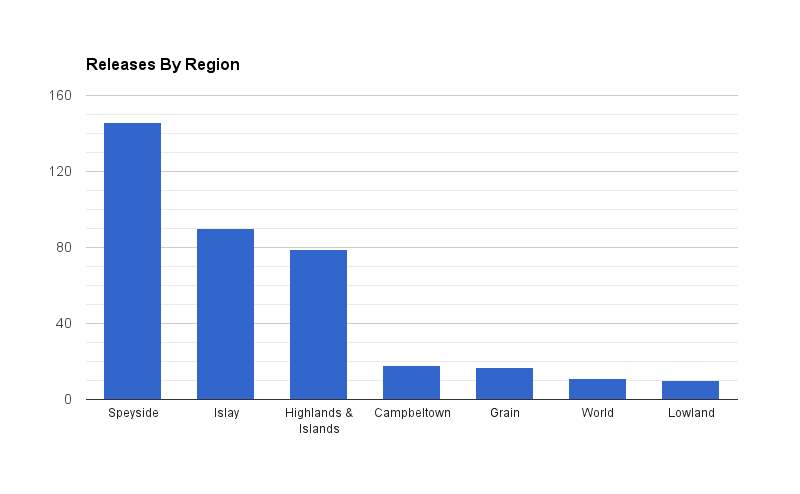

We’ve had releases from 17 separate listed regions, though that’s a bit misleading – There are four Highland regions, for instance (Highland Island, Highland Northern, Highland Eastern and Highland Southern), and four for Speyside. “Grain” is used as the region for all grain whisky, regardless of origin. Outside of Scotland, there have been releases from Ireland, Wales, Japan, the Caribbean and an Armagnac from France.

Speyside is the most common region, with 144 bottles (almost 39% of all releases) coming from the countryside around Scotland’s fastest-flowing river. Islay is next with 90 bottles, the Highlands and Islands have 81, and Campbeltown and the Lowlands have 18 and 10 releases respectively. Society lowland whiskies are more rare than grain or world whiskies.

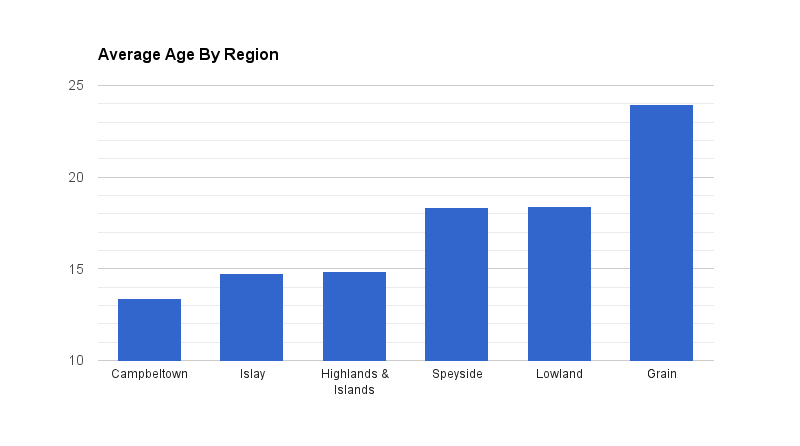

It’s interesting to look briefly at the average bottling age by region. Islay whiskies are often quite young, frequently under 10 years old, but there are a good enough number of older releases that the average is 15 years old in this dataset. Speyside has an average of 18 years – the extra time in the cask clearly benefits the rich flavours. The grain whiskies have an average age of 24 years, very high when compared to the single malts. The softer character of grain spirit seems to require extended aging to reach its peak quality.

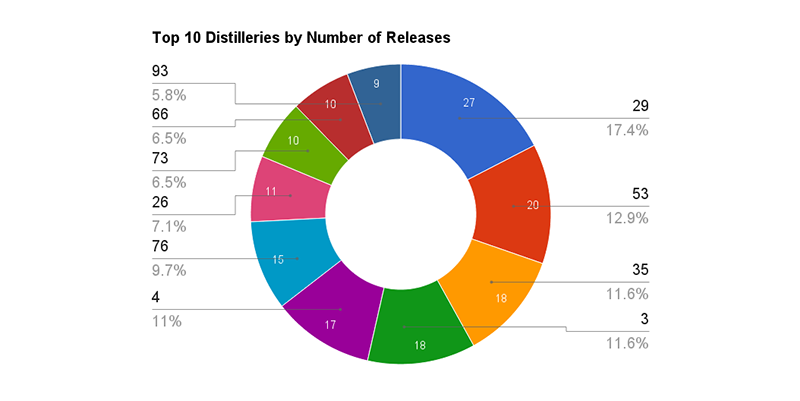

So after meandering around the whisky regions for a bit there, onto the distillery release data. With a clear lead, distillery 29 is in the lead with 27 releases. They come around on average every two outturns. The next-closest in terms of releases is another Islay favourite, distillery 53 with 20 bottlings.

Please note that the percentages listed in the following graphic are relative to the top 10 distilleries only. The top four distilleries represent around 22% of all bottle releases, not the apparent 54% the chart labels might lead you to believe! The top 10 distilleries gave us just under 42% of all bottles released.

Third place is a tie between yet another Islay, distillery 3, and of all places, distillery 35. They’re not a huge player in the single malt world, but they have a huge capacity and a relatively low-key blend (in the UK and North America anyway) so I imagine they have lots of spare casks to sell to the Society.

I’m very happy to see one of my favourites, distillery 4, in fifth place with 17 releases. We only got two this year though, down from four in 2014 and five in 2013, so I’m hoping we pick up that pace again. Another of my favourites is next, distillery 76, the Society releases of which have been incredibly good more or less across the board.

I hope to see continuing releases from new distilleries in the coming years, and personally I’d like to see the frequency of the 29s, 53s and 35s drop off a little bit. Clearly the first two are among the best distilleries in the world in terms of quality, so it’s hard to argue that we shouldn’t get any more with a straight face, but let’s see what some of the other Islays can do. I’m a particular fan of the 127s myself, which can always knock it out of the park in more ways than one.

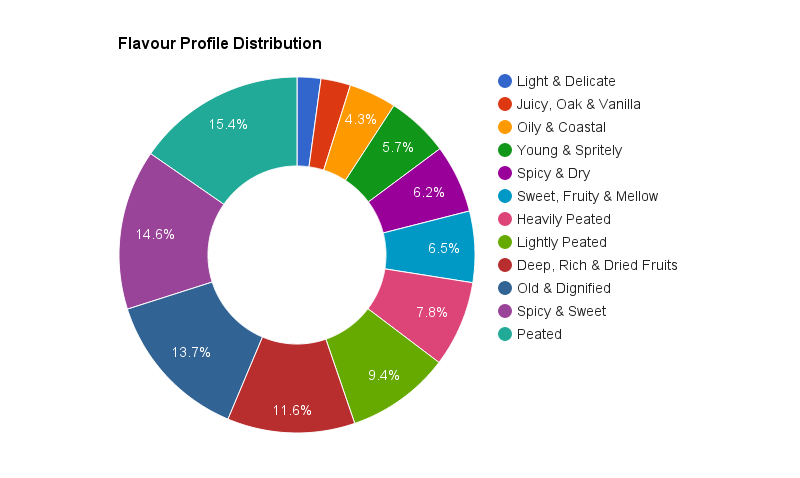

Finally, one last piece of analysis that I thought it might be fun to take a quick look at is the much-maligned “flavour profiles”. A profile is assigned to each whisky to give a quick idea of its general style, which is a fine idea in principle but the way they’re used feels pretty arbitrary. What exactly is the difference between “Peated” and “Oily & Coastal”? When is a whisky “Old & Dignified” vs “Sweet, Fruity & Mellow”? Can a dram be “Young & Spritely” and “Spicy & Sweet” at the same time? (Ampersands are used here as directed by the Society, by the way!)

Still, if nothing else it gives us something else to argue about at outturn tastings every month, and maybe that’s half the point. Here’s your quick look at the flavour profiles, with Peated leading the way and Light & Delicate bringing up the rear. Delicately.

The Rest

Apart from the bulk data analyses above, it’s interesting to see what we can find just poking through the individual bottle information. I’m curious to see if we can find any clues as to how the Society operates when choosing its casks, or deciding when to bottle them.

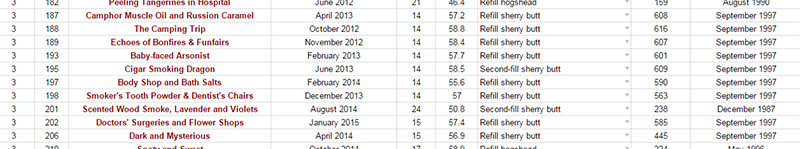

I’ve read that tasting panels are carried out blind, with judges scoring whiskies they know nothing at all about. Those that don’t meet a certain score boundary are either sent back to the warehouse to improve for a while, or rejected outright. While I’m sure this is true, there are some interesting data points. For instance, the run of distillery 3 bottles from 187-198 include seven that were all distilled in September 1997 and released at 14 years old. Did they all coincidentally reach their best around the same time?

There are similar runs in distillery 29’s bottles, and of the four distillery 31 casks we’ve had, all were from September 1988. Distillery 105 is similar too; we’ve had five bottles, all of which were from sherry hogsheads distilled in September 1983 and released at 28 years of age.

I have no idea how the SMWS obtains its casks, but it seems likely to me that these cask runs were bought by the Society already matured, brought out at judging sessions for the first time almost immediately, and all were rated over the releasable score right away. Even if I’m totally wrong, it’s fun (maybe only to a certain type of person!) to read through the data and try to pull out little bits of theory like this.

The End

Thanks for getting this far, if indeed you did. If you have any ideas for more things to comb the data for please let me know here or on Twitter (@measureofwhisky). I’m sure there’s more to find, and even more will become clear with the greater amount of data to come in future years. And thanks again to Rob & Kelly from the Canadian SMWS for doing such a great job, and for helping out with my little project here. Cheers!

Great work thanks